Minnesota's northern boundary was created by the Treaty of Paris of 1783 when Great Britain recognized United States' independence. The boundary would run from Lake Superior by an all-water route to the northwest point of Lake of the Woods then proceed due west to the Mississippi River, which at the time formed the western boundary of the United States.

Minnesota's northern boundary was created by the Treaty of Paris of 1783 when Great Britain recognized United States' independence. The boundary would run from Lake Superior by an all-water route to the northwest point of Lake of the Woods then proceed due west to the Mississippi River, which at the time formed the western boundary of the United States.Unfortunately the signers of this treaty didn't realize that the Mississippi River ended south of the Lake of the Woods so in the Treaty of 1818 they fixed the international border at the 49th degree parallel.

The eastern border is follows the Mississippi River north to until veers east along the St. Croix river and then due north to the western edge of Lake Superior.

The southern border was much easier following a straight line between itself and Iowa at 43º 30′ N.

The western border looks as boring as southern border at first glance. It goes straight north from its border with Iowa then follows the Red River north to Canada.

The western border looks as boring as southern border at first glance. It goes straight north from its border with Iowa then follows the Red River north to Canada.

The thing that interested me was seeing apparent connection between the Mississippi River and Red River. The river that connects them on the map above is the Minnesota River but that confused me as I knew the Red River flowed north to Lake Winnipeg then into the Nelson River and eventually into the Hudson Bay.

That really confused me. Could you take a canoe and paddle south from Hudson Bay, along the Nelson River, through Lake Winnipeg, along the Red River to the Minnesota, then to the Mississippi and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico?

That seemed impossible as everyone knows that a river can't flow in two directions at the same time. As I looked for an answer on Google Maps I struggled to find where one river stopped and the other began. They seemed to be one continous river.

The answer is actually in the two maps above but I needed to do more research before I figured it out. One thing that started to clear things things up for me was Google Maps. That tool is a godsend if you are curious about topographic detail in an area. The place where the rivers met was in Browns Valley, Minnesota but seeing that didn't give much insight to answer my question.

|

| Traverse Gap |

It did answer my question about the canoe. You can paddle from Hudson bay all the way to the Gulf of Mexico as long as you are willing to do a short 'traverse' in Browns Valley.

As you can see in the map above, Lake Traverse (part of the Red River watershed) is at the top of the map above and the Little Minnesota River is near the bottom. The two water sources are separated by less than a mile. If you are observant you might also see something else on the map that interested me a lot more which relates to the title of this article.

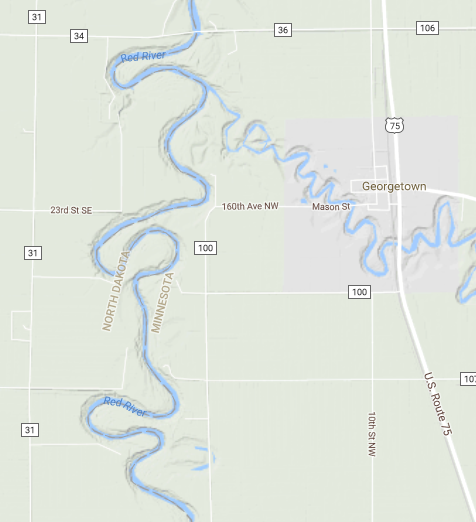

Here are a couple more maps of the Red River (and tributaries) leading to Browns Valley. Each map is further south and closer to Traverse Gap. See if you notice something odd.

|

| Red River in Georgetown MN near Fargo, ND (90 Miles North of Browns Valley) |

|

| Red River Tributary in White Rock, SD (25 Miles North of Browns Valley) |

|

| Lake Traverse (Just north of Browns Valley) |

To give you a little perspective, the above images are approximately 2 miles x 2 miles (except Traverse Lake). Did you noticed anything strange? Did you notice the narrow deep cut valley that broadens the closer you get to Browns Valley?

The reason is more apparent as you move south past Browns Valley. Here's screen captures of the Minnesota River (and tributaries) to the south.

|

| Minnesota River near Big Stone City, South Dakota (28 Miles south of Browns Valley, MN) |

Do you see it now?

The Red River maps north of Browns Valley are approximately the same perspective as the ones south on the Minnesota River.

I will give a hint. The valley south of Browns Valley is much wider than the current Minnesota River could ever carve. If you want to explore yourself you can goto this Google Maps link to see for yourself as it is hard to miss once you move the map around the screen.

Of course that does little to answer the question unless you already have a good understanding of North American geologic history.

Most Americans know Minnesota's nickname is the Land of Ten Thousand Lakes and for good reason. The official count of their lakes as published by the state is 11,842 lakes greater than 10 acres in size. The only state with more is Alaska.

Lakes are usually formed in following ways -

- Tectonic - Movement of tectonic plates trapping an ancient ocean (Dead Sea, Great Salt Lake)

- Volcanic - Dormant/inactive volcano leaves behind a caldera and fills with water (Crater Lake)

- Fluvial - Created by running water usually left behind by rivers that change directions

- Landslide - Earthquake moves land to dam water

- Glacial - Glaciers carve the land leaving behind gouges which fill with water (???)

Lakes have a life cycle just like any other geologic feature. Given enough time, all lakes will disappear as geologic activity along with sediments and organic materials cause them to turn into marshland and eventually disappear. Given that lakes are continually disappearing, a location with a numerous lakes must have had a recent event to allow them to form all at once. In fact there is only one thing that can create the number of lakes we see in Minnesota.

Glaciers. More to the point, the Laurentide Ice Sheet.

|

| Maximum extent of the last ice age around 21,000 years ago |

Glaciers are the answer to most questions when speaking to the geology of the Northern United States. As you can see quite plainly in the graphic to the right, the extent of the glaciers created the current path of the Missouri River.

Anyone that has visited Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois can clearly see a difference between the northern and southern portion of those states. The northern parts of those states are flat with rolling hills ; the south is quite hilly. That's all due to glaciers.

Anyone that has visited Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois can clearly see a difference between the northern and southern portion of those states. The northern parts of those states are flat with rolling hills ; the south is quite hilly. That's all due to glaciers.

Unimaginably huge ice sheets covering millions of square miles and thousands of feet tall moved south out of Canada at the beginning of the last ice age starting about 40,000 years ago reaching its maximum extent similar to picture to the right about 21,000 years ago. As the planet warmed, the ice sheets stopped their march south then started to retreat. As you might imagine it takes a while to melt ice over a mile thick.

One thing I never considered is what happens to all the water after it melts. At first, water from the melting ice sheet flowed south to existing rivers in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. The problem occurred when the glaciers melted to the other side of the continental divide.

This is a great map of North America that shows our current continental divides, i.e. where every drop of water will eventually end up assume it doesn't evaporate. Rainfall east of the yellow line in the Eastern United States ends up flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. East of the red line and south of the green line ends up in the Gulf of Mexico. Water north of the green line and south of the blue line ends up in Hudson Bay.

|

| Ancient Glacial River Warren |

Have you seen the problem?

As the ice sheets melted and retreated over the Laurentian (green) continental divide, the water had no place to go. A literal mountain of ice blocked its normal path to Hudson Bay.

Do you see the green line crossing a familiar point on western border of Minnesota on the map above?

Around 12,000 years ago, the water continued to melt and a small lake formed on the Hudson Bay side of the continental divide. As the warming continued, water topped the lowest point of the Laurentide continental divide at Browns Valley causing a rush of water to scour the Minnesota River valley for hundreds of miles and then do the same thing to the Mississippi River for another hundred miles. If you take another look at the google maps above or at this link, it is easy to see the damage done to the terrain thousands of years later.

This paper from Michigan State goes into much more detail on the deluge, Glacial Lake Warren, and Lake Agassiz than I ever could hope to match. Take a look if you are interested in a deeper dive on the subject.

Seeing the maps made me wonder as some some theorize that the first Native Americans made their way into Minnesota soon after the glaciers melted. That begs the question.

- Were people living along the Minnesota river when it first flowed down the valley?

- What about further down the Mississippi?

- What must these people have thought as a small river quickly transformed into a maelstrom a mile wide?

I would imagine the water flow would slow every winter than return with a vengeance in the spring and summer melts. I don't think many other geologic events could ever top this annual spectacle.

Scientists are not sure exactly how long Glacial River Warren (the name geologist gave to the widened Minnesota river) ran but the best estimates it continued off and on for about 2,000 years until about 9,400 years ago. A combination of accumulated silt in the Red River Valley and other outlets to the Mississippi and the Great Lakes caused the river flow to stop completely.

Scientists are not sure exactly how long Glacial River Warren (the name geologist gave to the widened Minnesota river) ran but the best estimates it continued off and on for about 2,000 years until about 9,400 years ago. A combination of accumulated silt in the Red River Valley and other outlets to the Mississippi and the Great Lakes caused the river flow to stop completely.

As the ice sheet melted further it created a massive lake - Lake Agissiz. At one point this lake was the largest fresh water lake in the world, larger than all the Great Lakes put together, stretching from Minnesota almost to Hudson Bay.

As the earth's crust slowly rebounded after the weight of the ice was gone, the land slowly rose causing most of Lake Agissiz to disappear but it is not gone completely. Lake Winnipeg is the remnant of a mighty ancient lake that once carved a river valley.

Who said geology wasn't fun?

Who said geology wasn't fun?

No comments:

Post a Comment